Why doesn’t French sound like it’s spelled? A look at the evolution of French pronunciation

If you’ve ever looked at a French word and thought, “That doesn’t read as it sounds?” You’re not alone. With its silent letters, nasal vowels, dropped endings, and accents that don’t always follow a clear logic, the French language often feels like it’s hiding its sounds behind a mist of orthographic fog.

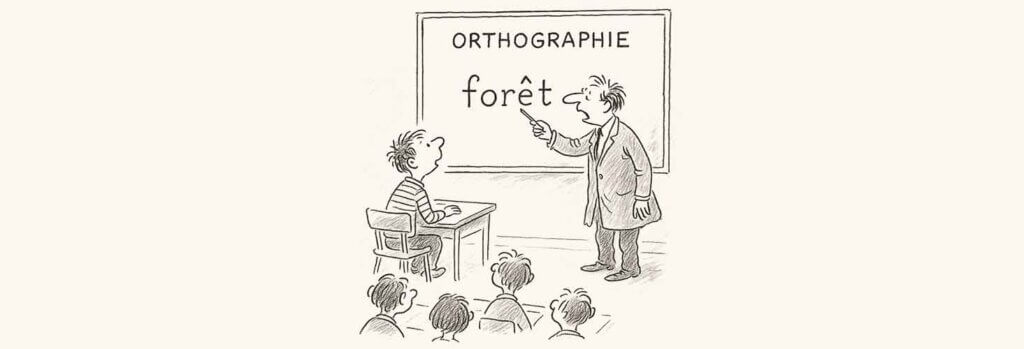

Take the word forêt (forest), for instance. Why the little hat on the ê? Where did the s go? And why does the t barely whisper itself into existence?

To understand why modern French often doesn’t “match” its spelling, we need to take a step back— at least three centuries back, in fact. French pronunciation has changed dramatically over the last 300 years, but the writing system has largely stayed the same. The result? An often confusing historical mismatch, at least for people learning French.

The great phonetic shift: Sound changes over time

Languages are living systems. They evolve constantly, especially in how they sound, and over the centuries, the French language has undergone significant phonetic simplification.

Three major trends have defined the shift in pronunciation:

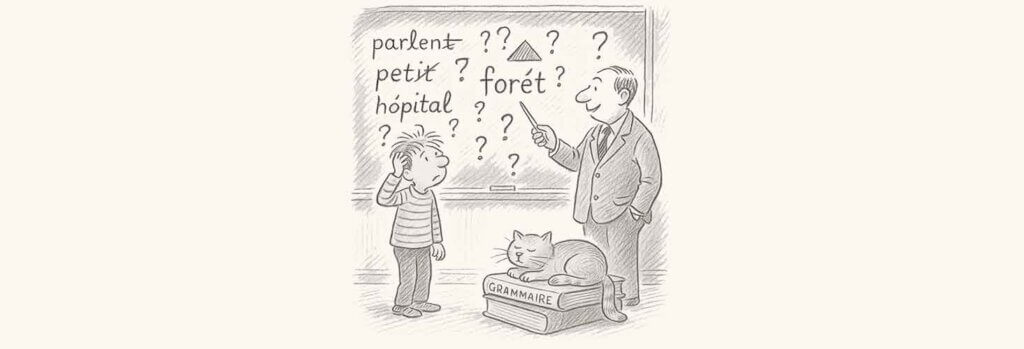

Loss of final consonants: Words once pronounced in full are truncated in everyday speech. Parlent becomes parle, petit becomes pti, vous often becomes vu. Many final consonants that appear in writing have disappeared in speech, except in cases of liaison.

Nasalisation and vowel reduction: Vowels have evolved from clearer, distinct sounds to more nasal and centralised ones. Bon and bien have nasal vowels that did not exist in the same form in Old French. Over time, multiple vowels collapsed into fewer, broader categories.

Syllabic simplification: Many formerly multi-syllabic words are often compressed in spoken French. Elisions and reductions, like je ne sais pas, become chais pas. This phonetic erosion increases spoken fluency but creates distance from the written word.

When spelling froze: The rise of standard orthography

While the form of French pronunciation has continually evolved to become the French language we know today, French spelling has stayed behind, largely codified and frozen in the past.

Academics and grammarians have attempted to standardise contemporary spoken French with its written counterpart, especially under the eagle-eyed guidance of the Académie Française.

Much in the image of the Académie Française though, spelling reform has often been conservative and slow, prioritising etymology (origin) over phonetics (sound). This has meant preserving Latin roots and older spellings despite phonetic speech changes.

For example:

- Estude (Old French for “study”) became étude, maintaining the Latin root studium, but with a new pronunciation.

- Hospital became hôpital, still recognisably Latin, but the way it’s said now—/opi?tal/—is quite distant from how it would have been spoken in the past.

The circonflexe: A hat with its history

An interesting example of the spelling pronunciation gap is the accent circonflexe (ˆ). This hat looking symbol may seem decorative, but it’s a historical marker, an indicator of a sound that once existed.

In many cases, the circonflexe marks where an “s” used to be in the Middle Ages.

Compare:

- forêt ? forest

- hôpital ? hospital

- hôte ? hoste (host)

- bête ? beste (beast)

In Old French and early Modern French, that “s” was pronounced. But over time, it fell out of speech. Rather than completely erase it from the writing system, grammarians left behind the accent as a signal of its past presence.

So, the circonflexe is a linguistic fossil: a reminder that spelling once traced pronunciation more closely than it does today.

Why the written language stayed behind

Why didn’t French spelling evolve with the spoken language?

The answer lies in social and political priorities:

- Prestige and identity: Standardised spelling became a marker of education and refinement, especially among elites. Changing it too often would undermine that prestige.

- Printing and publishing: Standard forms became necessary for consistency once printing became widespread. Reforming spelling would have meant economic disruption, effort, and confusion.

- Centralised language policy: The French state has been deeply invested in l’unité de la langue française, particularly since the 17th century. Reform was often seen as disorderly or populist.

Spelling reforms in modern French (notably in France in the 1990s) have been minimal and often resisted. For most speakers, spelling remains a badge of education rather than a mirror of speech.

The 1990 reforms proposed reducing the use of the circonflexe on “i” and “u” in cases where it no longer affected pronunciation or meaning. The change sparked a mini revolution in academic and literary circles. While the simplified spellings are officially accepted, many teachers and language purists continue to prefer traditional forms. As a result, the reform has seen only partial and often reluctant adoption.

What this means for French language learners

This historical disconnect can be frustrating for people learning French, even those at an advanced level who still find French surprisingly unfamiliar. Why spell a word with so many letters if half are silent? Why add a final letter that’s never pronounced?

But there’s a silver lining:

- French pronunciation is more regular than it seems. Once you learn the patterns—like silent final consonants, nasal vowels, and elisions—you’ll realise that French pronunciation is phonetically logical, just not always visible in the spelling.

- Spelling preserves meaning and history. Words that sound the same (vers, verre, vert, ver) are distinguished in writing, helping with comprehension and etymology.

- Listening matters more than reading. For fluency, focus on the spoken rhythm of French. Written forms can be decoded later.

Perhaps most importantly, the complexity of French spelling does not reflect how people speak—it reflects how history speaks through the language.

A living language, still evolving

Even today, pronunciation continues to shift, especially among younger speakers and in global French varieties. Many now omit “ne” entirely in casual speech: instead of saying je ne sais pas (“I don’t know”), it becomes simply “chais pas” or “je sais pas / j’sais pas“. Phrases are shortened, words blend, and spoken French becomes faster and more fluid. Meanwhile, spelling remains slow to adapt, reflecting older, more formal structures.

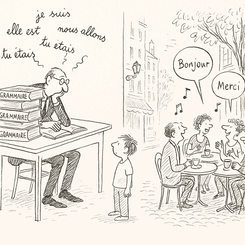

This means that French learners—and even native speakers—always balance two systems: the phonetic reality of modern speech and the historical formalism of written French.

While that balancing act can be difficult, it’s also part of what makes French culture so rich, layered, and deeply tied to its past.

***

French lessons or learning on your own: Why you should prioritise listening and speaking

Because French pronunciation has drifted far from its spelling, learners face a double challenge: decoding written words and recognising them when spoken. This is why it’s essential, especially for anyone trying to talk in French confidently, to prioritise talking and listening, not just textbook exercises.

To understand native French speakers – Stop focusing on the rules

Too many French schools still rely heavily on written materials. They focus on reading texts and memorising vocabulary lists, often at the expense of real-world listening practice. The result? Students who might write well but freeze when faced with a native French speaker in conversation.

Here’s the real issue: students often hear overly articulated French in classrooms. Whether it’s well-meaning teachers, classmates, or even a friendly server at a café, people offering tips on pronunciation tend to over-enunciate, stretching every syllable in a teaching style that often doesn’t reflect natural conversation. While this helps at the beginning, it can give a false sense of clarity. Spoken French, especially in natural conversation, moves quickly. Words melt together. Silent letters disappear, making it easy for learners to have a hard time catching individual sounds.

If students never train their ear to this living rhythm, they struggle to understand even basic phrases.

So, what’s the solution?

Learning French: Practice makes perfect—but with the right kind of practice

Yes, practice makes perfect—but it matters how you prepare and what kind of practice you do. It’s a combination of skills and tools. To improve your speaking, you need to spend time talking in French, even if you make mistakes. To improve your listening, you need to listen actively.

That means immersing yourself, even with a busy schedule, in the sounds of native French speakers, through real conversations first and then through podcasts, movies, and TV shows. Passive exposure isn’t enough.

When it comes to writing, it’s the same principle. Write regularly. Don’t just copy sentences—create them. Over time, you’ll build the internal reflexes and innate knowledge that native speakers have.

But beware: focusing only on reading and writing without building pronunciation skills can lead to internalising the wrong sounds.

Why? Because when you read in a new language, you also “hear” the words in your head. If you haven’t heard those words spoken correctly, your internal monologue can reinforce incorrect pronunciation. That’s why listening and speaking early—and often—is essential. It’s how you lay the foundation for true fluency.

Talking should be fun, not something to fear

Many learners have a real fear of using the language aloud. They are afraid of sounding silly or getting the accent wrong. But here’s the truth: your progress depends on those moments. You have to get things wrong before you get them right. Making mistakes is how you learn —and even more so if your willing to repeat and refine each attempt.

And talking doesn’t need to feel like a test. It can be engaging. It can be playful. Some of the most memorable French courses are free and happen outside formal French courses— in real life with friends, during travel, with your partner or wife, or while ordering lunch. If you talk in a language, you’ll see that the native speakers around you aren’t expecting perfection. They’re happy to be understood and value your effort and appreciation of their language.

French isn’t phonetic—and that’s okay.

Unlike Spanish, Italian, or Portuguese, which are mostly phonetic and read much as they’re spelled, French follows a different path. Once you grasp the difference between, say, the Spanish “j” and the English “h”, Spanish spelling becomes predictable. Not so in French.

French writing hides layers of history. And because the language continues to evolve, what you see isn’t always what you get. That’s why listening is key, not just as a skill, but as a way of understanding the soul of the French language itself.

In short? To truly speak French, don’t rely solely on your dictionary, your favourite language-learning site, or classroom exercises. Listen often. Speak boldly. Laugh at your mistakes. And above all, stay curious. This isn’t just about completing French courses—it’s about stepping into a living, breathing world of sound, rhythm, and human connection.

French isn’t hard—it’s just different. And once you learn to listen, that difference becomes part of the magic.

Conclusion: The echoes of an older French

The disconnect between modern French pronunciation and spelling stems from historical pronunciation, the rapid evolution of spoken French, and the slower pace of spelling reforms. Many of the silent letters and accented vowels aren’t meaningless—they are remnants of a version of French that once corresponded closely with how it was written.

As pronunciation changed, spelling didn’t always follow. But in the layers of spelling, we find stories of lost “s” sounds, of vanished consonants, of choices made by writers, academic, and grammarians long ago.

And maybe that’s the real lesson. French isn’t just a language you learn—it’s a language you evolve through. And in every oddly spelt word, a little piece of history survives.