Guide to French Articles and other Determiners: Definite, Indefinite, Partitive, Possessive, and Demonstrative

Why the French Language Insists on Measuring the World Before Speaking It

Understanding definite, indefinite, and partitive articles in the French language is more than just learning grammar. It’s learning how to measure reality before you speak it. Unlike English—where a noun can appear bare and undefined—French forces you to decide: is it le pain (the bread we know), un pain (a loaf), or du pain (some bread)? Before you even name a thing, French demands you weigh it.

French, unlike English or Russian, Turkish, or Chinese, makes you perform a small act of accounting before naming a noun. Is it specific? Countable? Known to both speaker and listener? Each noun’s article acts as a tiny label of status. This system—built on definite, indefinite, and partitive articles—defines how French sees the world.

Let’s take a tour of these linguistic gatekeepers.

Introduction – Article summary

When you learn a language, of course, rules matter—but they can also feel overwhelming. At My Linguistics, our approach to languages, in this case French, is not only about learning the rules of grammar but rather about understanding the cultural logic behind them.

When learners understand the cultural linguistics of French—how grammar reflects different ways of seeing the world—it becomes much easier to grasp language-specific grammatical concepts, such as the widespread use of articles. In some languages, articles don’t even exist, which makes using them in French seem even more unusual.

In French, every noun—everything that can be named—must be accompanied by an indication of its quantity, even if that quantity is zero. Whether it’s un ami, des amis, une amie, or du pain, French insists on quantifying existence.

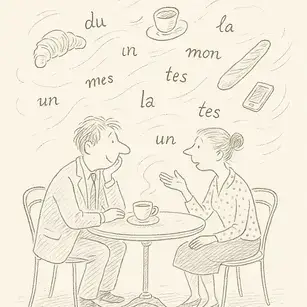

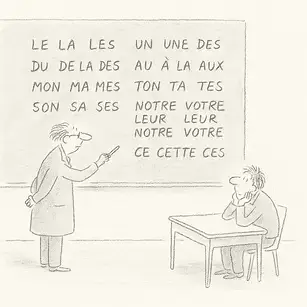

While this article focuses on articles as the main example, it’s important to note that the same function of defining and quantifying nouns also appears in other determiners, such as possessive and demonstrative adjectives. Like articles, these words — mon, ton, son, or ce, cette, ces — reflect the French language’s instinct to specify relationships and boundaries before naming a thing.

Key Facts to Remember

- French always requires an article before a noun. Unlike English or Russian, a noun cannot appear bare in a sentence.

- The definite article (le, la, les, l’) is used for both specific references and general statements (J’aime le café).

- Partitive articles (du, de la, de l’) express an undetermined amount of an uncountable noun (Je veux du pain).

- In negative sentences, partitive and indefinite forms reduce to de or d’ (Je n’ai pas de lait).

- Article choice depends on gender, number, and sound. A feminine noun starting with a vowel or silent h uses the masculine form for euphony (mon école, l’homme).

Definite and Indefinite Articles

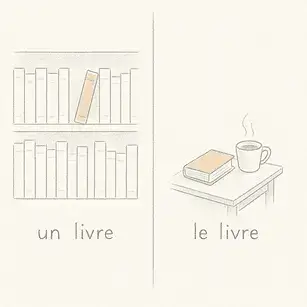

1. Les articles définis — French Definite Articles – The Known Quantities

Le, La, L’, Les are French definite articles, also called articles définis. A definite article tells you that a specific noun—one already known or identifiable—is being referred to.

Examples:

- Le chat – the (male) cat you already know. (masculine singular noun)

- La chaise – the (feminine) chair.

- L’école – the school; l’ is used before a vowel sound.

- Les étudiants – the students (plural noun).

The definite article contractions in French (like à + le = au, de + le = du) make these forms even more fluid. Each definite article marks a specific person, specific noun, or specific object already known to both speaker and listener.

Definite articles also express things in a general sense: J’aime le café (I like coffee in general). In English, you might drop the article, but in French, the definite article stays—because every noun needs its form.

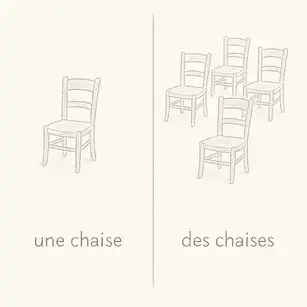

2. Les articles indéfinis — Indefinite articles – The New Arrivals

Un, Une, Des are indefinite articles. An indefinite article introduces something new to the conversation—a noun that hasn’t been mentioned before.

Examples:

- Un chat – a cat (masculine singular).

- Une chaise – a chair (feminine noun).

- Des étudiants – some students (plural form of the indefinite article des).

French indefinite articles work opposite to the French definite articles. While the definite points to something known, the indefinite points to something new or undefined.

Gender and number matter: masculine, feminine, singular, plural—each combination gives the indefinite article a different shape. Every noun’s gender and number determine its form.

3. Les articles partitifs — partitive articles in French – The Slices of Reality

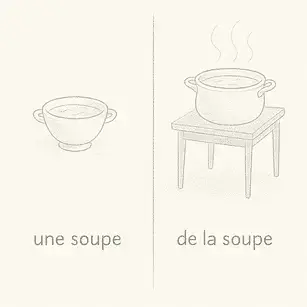

Du, De la, De l’, Des are French partitive articles (articles partitifs). The partitive article expresses an undetermined amount of something—usually uncountable nouns like water, bread, or coffee.

Examples:

- Je veux du pain. – I want some bread.

- Elle boit de la soupe. – She drinks some soup.

- Il y a de l’eau. – There is some water.

The partitive article indicates that you’re talking about a portion of a whole. When the noun becomes uncountable, French still demands precision. English would say “I want bread,” but French insists: Je veux du pain.

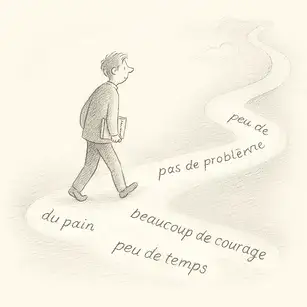

In negative sentences, all partitive forms collapse into de or d’:

- Je ne veux pas de pain. – I don’t want any bread.

- Il n’a pas de patience. – He doesn’t have any patience.

In short, pas de, peu de, and beaucoup de all mark amounts, even when the answer is not any. The partitive article reflects the French language’s need to measure everything—even absence.

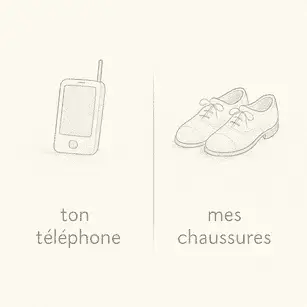

4. Les adjectifs possessifs — The Mine-Yours-His-Hers-Ours-Theirs

Mon, Ma, Mes / Ton, Ta, Tes / Son, Sa, Ses / Notre, Nos / Votre, Vos / Leur, Leurs

These forms tell us who owns what—but in French, ownership bends to gender and vowel sound. For instance:

- Mon ami – my male friend (masculine noun).

- Ma table – my table (feminine noun).

- Mon école – my school (note the silent h and vowel sound rule).

Sound trumps logic. A feminine noun that starts with a vowel takes the masculine singular form (Mon amie, ton école, son histoire) for euphony.

5. Les adjectifs démonstratifs — The “This-One-That-One” Crew

Ce, Cet, Cette, Ces – four forms of demonstrative adjectives that work like linguistic fingers pointing at specific nouns.

Examples:

- Ce garçon – this boy (masculine singular).

- Cet homme – this man (used before vowel sound or h muet).

- Cette femme – this woman (feminine singular).

- Ces femmes – these women (plural form).

Together with definite and indefinite articles, these four forms ensure that every noun is properly introduced.

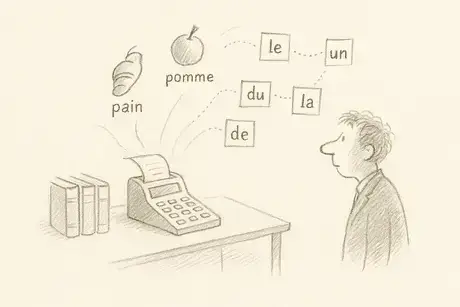

The Deeper Logic: Why French Does This

French grammar is really a philosophy of attention. Every noun’s article defines its boundaries. Before naming something, you must decide: is it unique, familiar, countable, abstract, or uncountable? Is it definite, indefinite, or partitive? Is it singular or plural, masculine or feminine?

In English, bare nouns like “bread” or “water” work fine. But the English definite article (the) and English indefinite article (a, an) don’t perform the same precision work. In French, the article is the meaning.

French insists on defining reality through its articles. It doesn’t allow a noun to appear without paperwork—its article is the declaration of how much reality it represents. That’s why learning definite, indefinite, and partitive articles is less about memorization and more about understanding that a noun sounds bare if unaccompanied.

While it’s quite simple to explain this, internalizing it can take a long time. However, being aware of this function of the language can help in acquiring it in the long term.

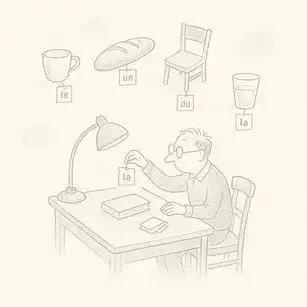

The Grammar of Quantity

Think of every noun as passing through a tiny calculator before joining a sentence.

- Is it known or unknown? Le pain (the bread) vs. Un pain (a loaf).

- Is it countable or uncountable? ? Un pain (one loaf) vs. Du pain (some bread).

- Is it singular or plural? Une pomme (one apple) vs. Des pommes (plural noun).

Each noun’s gender and number—masculine, feminine, singular plural masculine—must align with its article.

When you say Le vin, you mean the wine as a known concept. When you say Du vin, you imply some wine, an undetermined amount. And when you say Pas de vin, you define zero—a negative partitive article moment. French doesn’t let even nothingness go uncounted.

A Sentence is a Tiny Universe

Every sentence in French is a small act of classification. The definite article focuses the lens; the indefinite article opens new ground; the partitive article describes flow and portion.

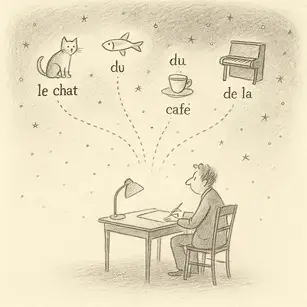

When you say Le chat mange du poisson, you’re saying: the specific cat eats some fish. The definite article (le) identifies a known or specific subject, while the partitive article (du) indicates an unspecified quantity of something (fish). Together, they show both familiarity (the cat) and scale (some of the fish, not all).

Compare that with J’aime le café or J’aime le vin—expressions using verbs aimer with definite articles to show general liking. But when you say Je veux du café, s’il vous plaît, you use the partitive article to request an undetermined amount.

Even musical instruments follow this logic: Je joue du piano, de la guitare. Every act of naming or playing requires an article. French insists on framing reality—never bare, always measured.

Why French Never (almost never) Drops Its Articles

The English article system lets nouns float naked: “I like bread.” The French definite articles and French partitive articles don’t. French requires specification before naming. Le pain, un pain, du pain—each phrase encodes precision.

Even the absence of a thing—pas de pain—is defined. The definite and indefinite articles map how French speakers perceive existence: each object, idea, or abstract noun must be either specific, general, or undetermined.

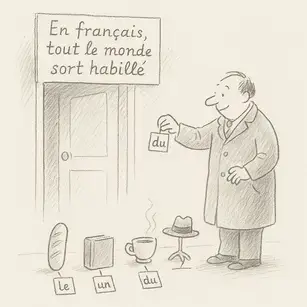

French is linguistic hygiene: every noun must be dressed before leaving the house. You wouldn’t say pain alone. You say le pain, un pain, or du pain. Even prepositions à and de fuse with articles to create harmony (au marché, du magasin).

The Exception to the Rule

As with most French grammar, even articles and determiners have exceptions. These occur when the noun no longer refers to a specific object but rather to a state, role, or identity. In such cases, French drops the article because what’s being expressed is abstract, habitual, or intrinsic—something that can’t be counted or specified.

You’ll find this in four main cases:

- Fixed expressions (J’ai faim, J’ai peur, J’ai rendez-vous) – idiomatic phrases where the meaning is treated as a single concept.

- Professions and titles after être or devenir (Il est médecin, Elle est chef de projet).

- Nationalities and religions after être (Tu es grecque, Il est catholique).

- Certain abstract or emotional states – when the noun represents a feeling, condition, or idea rather than a countable thing.

In short, French omits the article when a noun expresses a state, role, or identity—something a person is, feels, or embodies—rather than a concrete object or substance—something that exists in the world or can be measured or counted.

Even here, though, the exception proves the rule: the article disappears only when the noun stops naming things and starts naming essence.

From Concept to Reflex

The theory behind determiners can be explained in minutes—but integrating them can take years. Native speakers don’t calculate consciously whether a noun is masculine or feminine, singular or plural, definite or indefinite. They feel it.

With exposure, you’ll begin to sense it too. You’ll say du pain instead of le pain instinctively. You’ll say pas de problème, beaucoup de courage, peu de temps, because the rhythm of French measures reality automatically.

Every word, every form, every article—they all reinforce one philosophy: nothing in French exists without scale, ownership, and shape.

The Moral

In French, no noun is ever left vague. Every masculine or feminine, singular or plural noun must declare its category. That’s not just grammar—it’s a way of organizing reality.

To speak French fluently is to see the world as bounded, countable, and intentional. Every definite, indefinite, and partitive article helps us frame reality with precision. Language isn’t only what you say. It’s how precisely you see.

About My Linguistics

My Linguistics is a language training center based in Geneva, Switzerland. We’re passionate not just about teaching languages, but about understanding how people learn. Our mission is to explore the connection between learners, learning processes, and effective teaching strategies—to improve outcomes and create meaningful learning experiences.