Passé composé or imparfait: stop overthinking, start feeling time

This article is designed for learners who want to choose correctly between the passé composé and the imparfait in French usage and understand why the two differ.

When learners study French, one question comes back again and again:

Why are there two past tenses, the passé composé and the imparfait?

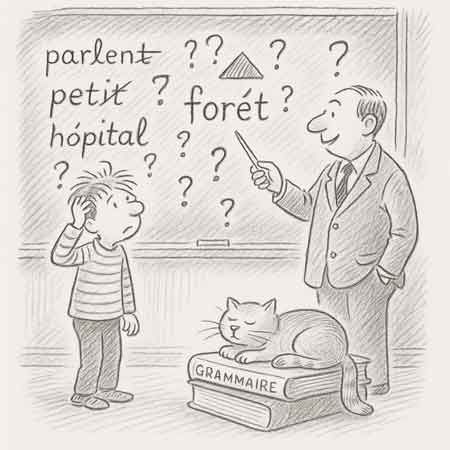

At first, learners want rules. They want logic. They want a checklist that explains which tense to choose, in which sentence, and at which moment. This instinct is understandable, especially for learners preparing for a French test or working through structured grammar explanations.

However, this method often causes more confusion than clarity. It is also where learners frequently make errors by depending on strict rules instead of understanding the meaning.

In addition to clear explanations of conjugation, learners benefit from a deeper understanding of how French conceptualizes the timing of actions.

Native speakers rarely stop to analyse meaning in grammatical terms or which tenses in French to choose from. The distinctions feel natural.

Passé composé vs imparfait: the core difference

The difference between passé composé and imparfait is mainly about how we see the action in time. In other words, the two tenses express actions differently in relation to time.

- The passé composé is a French past tense used to describe actions completed in the past, specific events, or a series of past actions.

The action is presented as a whole, with its beginning and end implicitly taken as defined, even if they are not mentioned. - Imparfait talks about a past action that is seen as open, as an ongoing situation, a habit, or a description in the past. We do not focus on its beginning or its end.

Both are past. Both are finished in reality. In both cases, the actions are completed in the past, but are framed differently. The difference is not temporal truth, but how the action is grammatically fixed or not fixed.

Passé composé vs imparfait: detailed explanation

Passé composé (auxiliary verb + le participe passé)

The passé composé is a compound past tense formed with a present tense auxiliary verb (auxiliary avoir or auxiliary être) plus a past participle (le participe passé). It is often compared to the English perfect tense, but the two do not function in the same way.

The choice of auxiliary depends on the following verbs used in the sentence.

It is used to express:

- completed actions

- specific events

- specific actions with a clear boundary

- actions anchored to a specific time, explicit or implicit

Examples:

J’ai parlé. – I spoke / I have spoken.

Nous avons parlé. – We spoke / We have spoken.

Vous avez fini. – You finished / You have finished.

Il a mangé. – He ate / He has eaten.

Il est parti. – He left / He has left.

Il / elle sont partis / parties. – They left / They have left.

In each case, the action is presented as a whole. The beginning and end are grammatically fixed, even if the sentence does not mention a time expression.

Imparfait

The imparfait describes past situations that are not grammatically closed.

It is used to:

- Describe ongoing or background situations

- Express habitual actions or repeated actions

- Provide background information

- Describe states, emotions, or conditions

Examples:

Je parlais au téléphone. – I was speaking on the phone.

Nous parlions souvent après le travail. – We often talked after work.

Vous finissiez tard le soir. – You were finishing late in the evening.

Il mangeait quand je suis arrivé. – He was eating when I arrived.

Il partait tous les matins à huit heures. – He used to leave every morning at eight.

Ils / elles partaient ensemble. – They were leaving together.

Il / elle partait toujours sans prévenir. – He / she always left without warning.

An example: eating and the phone

Let’s take a simple situation.

Il mangeait quand le téléphone a sonné.

He was eating when the phone rang.

Here is how the two actions are grammatically structured:

- Il mangeait

He was in the middle of eating. We do not know when he started. We do not know when he finished. The action is open and in progress. - Le téléphone a sonné

The phone rang. This is a single event. It starts, it happens, it stops. It interrupts the eating.

That is why French uses:

- imparfait for mangeait

- passé composé for a sonné

Now look at this sentence:

Il mangeait quand le téléphone sonnait.

This sounds unusual in most situations, and this type of mistake is quite common.

Why? Because using the imparfait for sonnait suggests that the phone was ringing continuously or repeatedly while he was eating. It no longer sounds like one single interruption. It sounds like background noise.

The tense changes the meaning because French grammatically encodes whether an action is delimited or non-delimited in the past.

Passé composé vs imparfait: Fixed actions vs background actions

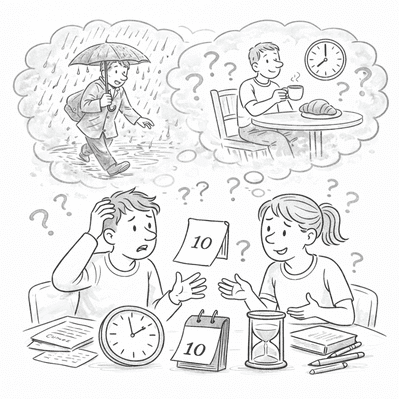

A useful way to think about it is this:

- Imparfait sets the scene.

It describes what was happening in the background. - Passé composé moves the story forward.

It introduces events that happen at a specific moment.

That is why interruptions are usually in the passé composé.

Another example: asking someone’s name

Look at this sentence:

Il a demandé comment elle s’appelait.

He asked what her name was.

- Il a demandé

Asking is a clear action. It happens once. It has a beginning and an end. - Comment elle s’appelait

Her name is general information. It is not a one-time action. It is a state or a fact in the past.

Now compare it with:

Il a demandé comment elle s’est appelée.

This does not mean the same thing.

Here, it would mean something like:

He asked what she was called at that moment, or what name she used at that time.

This version only makes sense in special contexts, for example if she changed her name.

When everything becomes vague

Now look at this sentence:

Il demandait comment elle s’appelait.

He was asking what her name was.

This sounds vague. It suggests repetition or background activity. Maybe he was asking several people. Maybe it happened over a period of time. The sentence does not tell us when exactly it happened or if it was a single, clear event.

That is the effect of the imparfait. It removes sharp edges. It makes things less fixed.

The link with English past tenses (and its limits)

English and French both use several grammatical forms to refer to the past, but they organise past reference differently.

English uses several grammatical forms to encode past reference, including:

· the simple past (he ate, she shopped), which can remain structurally underspecified with respect to how an action is framed

· auxiliary + past participle constructions (he has eaten, he had eaten), which encode additional information such as sequence, relevance, or discourse anchoring

French, by contrast, requires the speaker to choose between competing past forms—most notably passé composé and imparfait—to indicate whether a past action is grammatically delimited or non-delimited.

There is no French tense equivalent to the English past participle. The French passé composé and imparfait past tenses do not, fundamentally, function in the same way as the English past participle. It is not possible to say that a specific tense is equivalent to a French past participle. In the same way, there is no imperfect tense in English.

Why one-to-one translation fails

Because English often leaves the grammatical framing of a past action implicit, the same English past form can correspond to different French tenses, depending on usage.

Conversely, a single French tense can translate into different English structures, because English does not always encode the same distinctions morphologically.

This reflects different historical and usage-based developments in how the two languages structure past reference, not a grammatical inconsistency.

Minimal examples

English: I was thinking about it.

French: J’y pensais.

The English continuous form does not mechanically determine the French tense.

English: He has been speaking about you.

French: Il parlait de toi.

The English present perfect continuous does not map directly onto a French perfect form.

English: He lived in Paris for three years.

French: Il a vécu à Paris pendant trois ans.

A completed duration requires a delimited past in French.

English: He took them.

French: Il les a pris.

The placement of the direct object does not change the tense choice; the action is presented as a completed event.

One systematic pattern (illustrated)

For verbs expressing states, roles, or extended activities, the English simple past can correspond to either French past tense:

English: He worked in Geneva.

French:

- Il a travaillé à Genève. (bounded fact)

- Il travaillait à Genève. (background state)

This same pattern applies to live, teach, study, work, etc.

Important limits

This equivalence generally does not apply to:

- punctual verbs (arrive, stop, answer)

- interaction verbs inside the same clause (ask, say, tell)

In these cases, English does encode aspect (asked vs was asking), so the collapse is not possible.

Practical consequence for learners

English comparisons can help learners understand that the past is not a single category.

However, English tense forms cannot be used as a decision tool for French tense choice.

French past tenses must be selected according to how French grammatically structures past actions, independently of English labels.

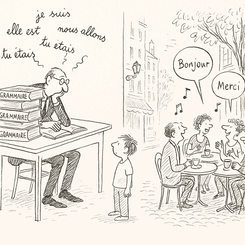

The key takeaway

The passé composé and the imparfait do not exist because French likes complexity. They exist because speakers need two different ways to look at the past.

- One way to show completed, specific events.

- One way to describe ongoing, habitual, or background situations.

If you try to memorise too many rules, you will slow yourself down.

If you focus instead on how an action is structured in time, your choices will become more natural.

Just like in English, the goal is not analysis.

The goal is intuition.

And intuition comes from exposure, examples, and practice, not from overthinking.

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

What is the difference between le passé composé and passé simple?

The passé simple is a literary tense. It appears in written narratives, not in spoken language. In modern speech, passé composé replaces it almost entirely.

How is the passé composé formed?

It is formed with an auxiliary verb (avoir or être) plus the past participle (participe passé).

Example: j’ai parlé, je suis allé.

What is an auxiliary verb?

An auxiliary verb is a verb used to form a compound tense. In French, the auxiliary verbs are avoir and être.

What is le participe passé?

Le participe passé is a non-finite verb form.

It is not a conjugation (it has no person or tense on its own), and it is not inherently an adjective.

It belongs to the verb system, but it can be used in different grammatical functions:

- Verbal function: with an auxiliary verb (avoir or être), it forms compound tenses such as the passé composé (nous avons demandé, elle est partie). In this use, it is part of the verb and does not describe a noun.

- Adjectival function: in some contexts, the same form can modify a noun and behave like an adjective (une question demandée, les lettres écrites). In this use, it agrees in gender and number because it describes a resulting state.

- Participial constructions: it can also appear inside verbal constructions such as ayant demandé, where it remains verbal and does not behave like an adjective.

In short, the participe passé is a verb form whose function depends on how it is used in the sentence, not a tense and not an adjective by nature.

Auxiliary avoir or auxiliary être? Which verbs use être?

In modern French, most verbs form compound tenses with the auxiliary avoir. A small, fixed group of verbs uses the auxiliary être instead. This is not a flexible choice: for each verb, the auxiliary is lexically determined and must be learned.

This group consists mainly of intransitive verbs that express movement or change of state, as well as all reflexive verbs. For practical learning, this set is usually reduced to a short list of high-frequency verbs, often memorised using the mnemonic Mrs Vandertramp.

Verbs that use être as an auxiliary (non-reflexive)

- aller

- venir

- arriver

- partir

- entrer

- sortir

- monter

- descendre

- naître

- mourir

- rester

- tomber

- retourner

- rentrer

- passer

- devenir

All reflexive verbs also use être (for example: je me suis levé, elle s’est trompée).

Why does agreement matter?

With être, the past participle agrees in gender and number:

elle est allée, elles sont allées (feminine plural).

What about irregular verbs?

Many irregular verbs have irregular past participles, which must be memorised: eu, été, fait, pris.

What is a direct object, and why does it matter?

When a direct object comes before the verb with avoir, agreement may occur:

les lettres qu’elle a écrites.

Does English present perfect equal passé composé?

No. Present perfect in English and French passé composé overlap partially but follow different grammatical logic.

What are Group 1, Group 2, and Group 3 verbs in French?

Most verbs in French are classified into three conjugation groups.

Group 1 verbs are -er verbs, which form the largest group and follow a regular conjugation pattern.

Group 2 verbs are -ir verbs that conjugate with -issons in the present tense. These verbs also follow a regular conjugation pattern.

Group 3 verbs include all remaining verbs. This group contains many verbs with irregular forms and does not follow a single conjugation pattern. It therefore includes what learners often experience as exceptions.

In simplified terms:

- Group 1 (-er verbs) are conjugated according to the -er model

- Group 2 (regular -ir verbs) are conjugated according to the -ir model

- Group 3 verbs include all remaining verbs. This group contains verbs with irregular forms and does not follow a single conjugation pattern.

Many main verbs in French, such as être and avoir, fall into this third group. These verbs are central to French grammar because they function both as lexical main verbs and as auxiliary verbs in compound tenses.

As a result, Group 3 verbs are frequent in everyday language and must often be learned individually.

This classification applies across tenses.

When should I use passé composé instead of imparfait?

Use the passé composé when the action is presented as a completed event or as a specific moment in the past, rather than as a background situation or habit.