Do you really need French grammar to learn French? Rethinking what matters most

Reimagining how we learn French

Let’s imagine something radical for a moment.

What if the way we teach French had evolved differently? What if, centuries ago, the guardians of the French language had made their decisions not at the desk but in the street?

What if French lessons didn’t begin with grammar at all?

What if, instead of formalizing verb endings based on Latin roots and literary tradition, they had based our learning of French on how it actually sounded when people used it?

Similar sounds, different rules

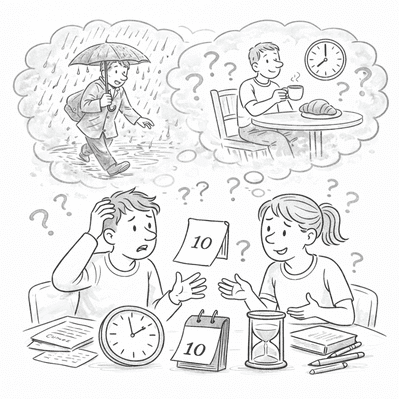

Maybe we wouldn’t have to deal with the headache of “je suis allé,” “elle est allée,” “ils sont allés,” “tu étais allé,” “j’allais,” and “nous allions”—all of which, despite their elaborate distinctions on paper, sound so remarkably similar in the mouth.

The vowel “é” (or something close to it) carries the weight of most of a tense system, with only the auxiliary verb doing most of the heavy lifting.

From the ear’s perspective, the passé composé and imparfait often blend. Additionally, spoken French often drops final consonants, neutralizes agreement endings, and simplifies grammatical complexity.

You begin to wonder: Are we teaching the language people talk—or just the rules they write down?

Key Takeaways

- Forget rote memorization; connect French words to real-life experiences and emotions.

- Listening is extremely important, perhaps even more important than speaking at first.

- Learning a language isn’t like a school test; it’s a journey.

- To really learn French, you’ve got to live it, not just study it.

- Focus on a natural, long-term approach to incorporating French into your everyday life, just as real life works.

The French Language: Phonetic reality vs. Grammatical fiction

Hearing French is simpler than seeing it

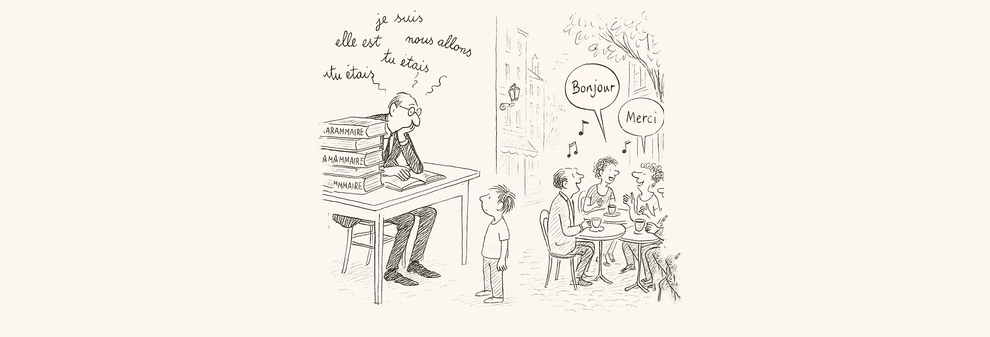

Here’s the truth that rarely gets acknowledged in a traditional language school setting: the spoken form of French is far more regular, fluid, and accessible than its written counterpart.

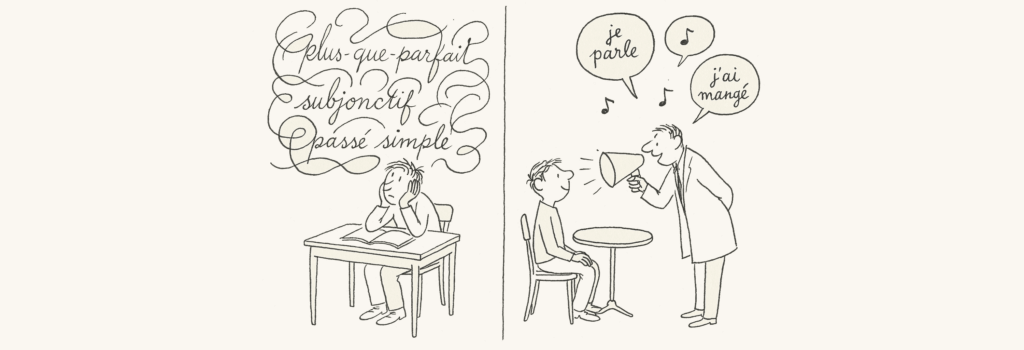

Many infamous French tenses that scare learners away—the subjunctive, the passé simple, the plus-que-parfait—are rarely used in conversation or are phonetically indistinguishable from simpler forms.

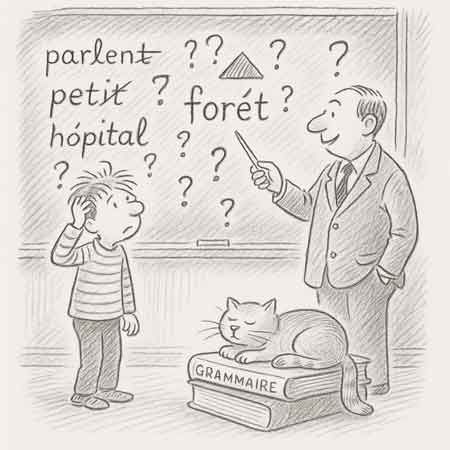

Take a sentence like “je parle en public” and its subjunctive counterpart “il faut que je parle en public.” In writing, the grammatical difference is clear—indicative vs. subjunctive. But the grammatical explanation detailing the difference between “parle” and “parle” and the presence of the que makes absolutely no difference in speech; they sound identical. The verb “parle” doesn’t change pronunciation.

This is to the extent that many learners actually learn the subjunctive naturally before they learn it academically and may deplore the fact that they do “not know it” because they don’t understand the rule.

Similarly, in phrases like “j’ai mangé,” “il a mangé,” and “nous avons mangé,” the difference lies mostly in the auxiliary verb. The past participle “mangé” stays the same, and for many learners, that’s the part they remember most.

French grammar—beautiful as it may be on paper—is often something you read; a visual system, not an auditory one. It’s designed for clarity on the page, not efficiency in the mouth.

French courses: The illusion of grammar as a starting point

Grammar before speaking: A backward approach

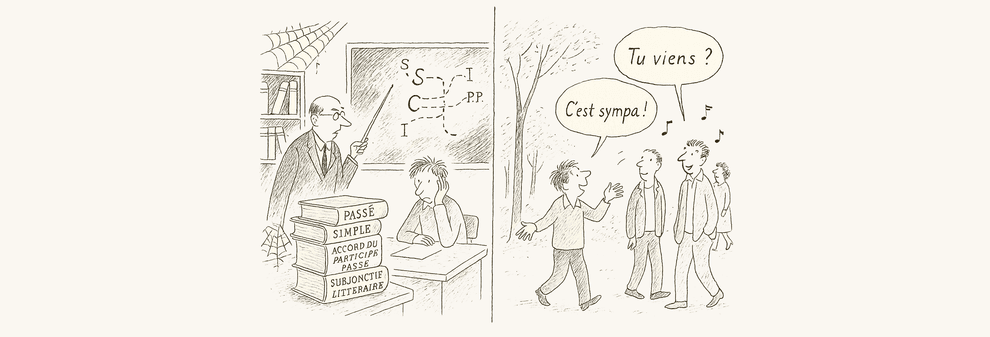

For decades, French courses and broader linguistic education have been built on a peculiar assumption: that grammar is the gateway to fluency. In many traditional classes, teachers often require students to complete grammar exercises, recite conjugation tables, identify verb groups, and memorize agreement rules before they’ve even begun developing real French language skills through conversation.

But this isn’t how we learn our first language. We don’t review grammar charts before we speak—we just speak, and patterns follow. And it’s certainly not how we acquire our second either, at least not naturally.

Just watch how children pick up speech through listening, play, and repetition—not by studying verb charts.

We don’t internalize grammar rules and then speak—we speak, listen, and interact, and over time, grammar emerges as a pattern our brains start to recognize.

The person who says “j’ai allé” instead of “je suis allé” isn’t failing—they’re communicating. They’ve grasped the essential idea: someone did something in the past. The details can be refined later, especially once they receive more input through experience.

But what’s dangerous is when learners hesitate to speak at all because they don’t yet “know the rules.” In this model, grammar becomes a gatekeeper, not a tool. That’s a problem.

Grammar as a retrospective, not a prerequisite

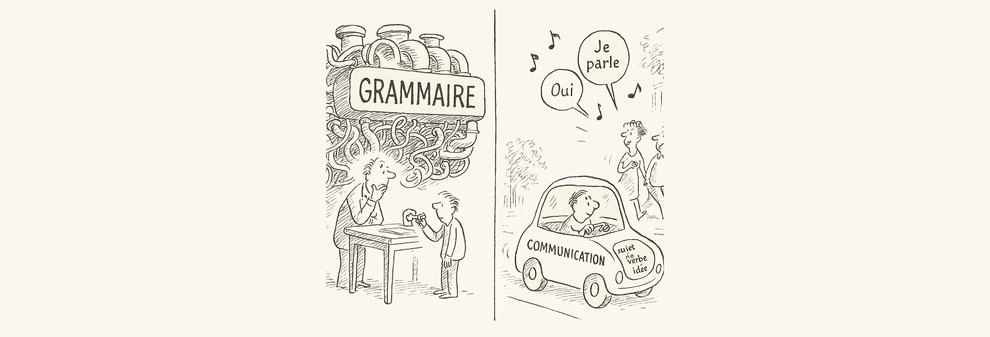

What if we stopped treating grammar as the foundation of language learning and started treating it as a reflection of something deeper: acquired language competence?

In this view, grammar isn’t the engine; it’s the dashboard. It helps us understand what’s going on under the hood, but it doesn’t make the car run.

Meaning comes before form

Many linguists—from applied theorists to neurologists—agree on this essential point: language is a system of meaning first and form second.

The structures we call “grammar” are real, but they are best learned through exposure, usage, and interaction, not as isolated abstractions.

This isn’t to say that grammar is useless when people learn French. It’s just not the best place to begin. For learners who are already speaking, grammar can help clarify recurring patterns or refine their style. But insisting on it too early—before learners reach a comfortable level of confidence—can delay the very thing it’s meant to support: communication.

French phrases: Why the phonetic approach works

A phonetic or sound-based approach to learning French flips the traditional model on its head. Rather than beginning with verb tables and gender rules, we begin with rhythm, stress, and intonation. Learners are exposed to high-frequency expressions, short dialogues, and authentic interaction. They imitate what they hear, make mistakes, and refine.

The reason this works is simple: speech precedes literacy. It always has. When learners focus on what they hear, they’re naturally tuned into the real patterns of the language, not the artificial ones imposed by the written form.

Spoken French simplifies the subjunctive

Consider how many French learners agonize over when to use the imparfait versus the passé composé, only to later realize that native speakers often blur the distinction in casual speech. Or how the much-feared subjunctive is introduced as a complex mood but rarely pronounced differently than simpler verb forms.

In these cases, the problem isn’t that learning French is too difficult. It’s that we’re teaching a version of French no one uses in everyday conversation.

Outdated grammar in a modern world

There’s a broader issue at play here: the lag between linguistic reality and pedagogical tradition.

Many of the grammar rules that dominate textbooks are relics. The passé simple, for example, is rarely spoken in modern French. It lives in literature, not in the living room. However, it is still taught in some beginner courses, despite belonging (if it belongs anywhere) at the advanced level of formal writing or literary study, as though mastering this grammatical tense were essential to everyday fluency.

French lessons – Obsolete rules still in the curriculum

Other rules—such as elaborate gender agreement in participles or obscure forms of the subjunctive—persist in teaching materials long after they’ve faded from spoken use. Their continued presence reflects more on academic inertia than linguistic necessity.

This creates a misalignment for someone whose goal is to speak French—not write novels or pass bureaucratic exams—because the tools they’re given don’t match the tasks they’re expected to perform.

Toward a more humane pedagogy

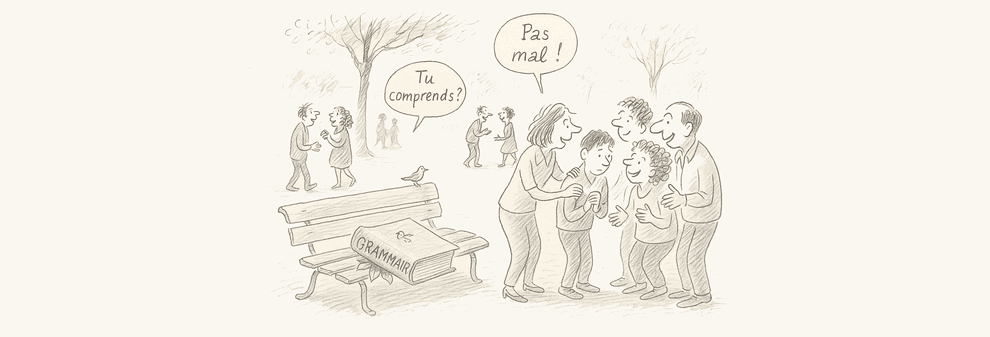

Language, at its core, is a human act. We speak to connect, share, ask, joke, and express need or delight. Speaking is social—and it should be fun, too. And this act of speaking relies first and foremost on sounds, phrases, and intent, not on approving a rulebook.

If we want to help learners learn French, we need to meet them where the language lives: in the ear, voice, and body. We need to let them speak before they’re “ready.”

We need to privilege understanding over correctness through listening, speaking, and interactive activities that reflect how people really use the language.

And we need to remember that most of the grammar we’re so attached to only matters after communication has already happened.

What should you look for in a French course?

Whether you’re looking for in-person classes or online French lessons, whether you’re comparing free or paid offers, or trying to find the right type of training, focus on one key thing: choose a method that exposes you to the language as it’s really used.

A strong course— in-person, online lessons, or a self-study plan—helps you use French in your everyday activities, focuses on French phrases rather than single words, builds your French language skills, and teaches the overall shape of the language before diving into formal grammar rules.

If you’ve already taken a French course or studied on your own, but now want to prepare for more formal writing or improve your spelling, look for a course that helps you make sense of grammar as a tool, not as a subject of analysis. The goal is to review what matters most for communication.

While written and spoken French do differ, especially in formal contexts, they still follow the same essential rules of syntax. Many learners who struggle with writing do so because they still struggle to speak correctly. This is to say their core struggle is form rather than spelling. Speaking well first will often help your writing fall into place.

Final thoughts: Learning to speak, not the system

The question isn’t whether grammar exists. It does. But the more helpful question is: when does grammar matter in the learning process?

For those just starting, the answer is often: not yet.

So, if you’re a learner hesitating to speak because you’re unsure of the agreement, the auxiliary, or the tense—forget it. Say it anyway. Get the sound out. That’s how you improve—by using the language, not waiting until everything feels perfect. Let the system emerge later.

The rules can wait. The conversation can’t.

Further Reading

This is just the tip of the iceberg—these texts make for engaging and thought-provoking reading if you want to explore this subject in more detail.

Krashen, S. (1982) – Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition

Classic argument for learning through meaningful input, not grammar drills.

Read online

Bygate, M. (2013) – Effects of Task Repetition on the Structure and Control of Oral Language.

Shows how fluency and grammar emerge through speaking, not pre-teaching rules.

Second Language Research, 12(3)

Ellis, R. (2006) – Current issues in the teaching of grammar: An SLA perspective. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 83–107.

Explains why grammar is best introduced after communicative ability.

DOI: 10.1177/1362168806066769

About My Linguistics

My Linguistics is a language training center based in Geneva, Switzerland. We’re passionate not just about teaching languages, but about understanding how people learn. Our mission is to explore the connection between learners, learning processes, and effective teaching strategies—to improve outcomes and create meaningful learning experiences.