The CEFR Explained: Understanding the A1 to C2 Language Levels

The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) is the most widely accepted international standard for describing language proficiency. Created by the Council of Europe, it defines six CEFR levels that describe what learners can do in any foreign language, from basic communication to advanced academic and professional interaction.

This European Framework of Reference has become the foundation for language learning, language assessments, and curriculum development across languages spoken in Europe and beyond. It is also applied in non-European languages such as Arabic and Japanese, making it a truly global scale for describing and comparing language ability.

Key Facts About the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR levels)

- The CEFR defines six levels (A1–C2) that show progress from very basic phrases (A1) to advanced and precise use of language (C1/C2).

- It was developed by the Council of Europe in the 1990s to create a shared framework for describing and comparing language ability, and to provide a common basis for comparing different language qualifications across Europe.

- Over 40 European and non-European languages have been mapped to the CEFR, with many teaching programs and exams referencing its levels.

- The CEFR has been translated into more than 40 languages and is now used across education and testing systems worldwide, well beyond Europe.

- The CEFR levels are used by educational institutions, exam providers, and employers worldwide as a reference point for assessing language ability and ensuring comparability across systems.

1. Purpose and Origins – A common reference for languages

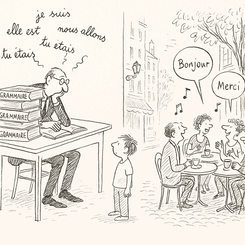

The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages was developed in the 1990s by the Council of Europe to create a shared system for describing and comparing language proficiency across countries. Its aim was not to dictate how languages should be taught, but to give learners, teachers, and institutions a common language for talking about language itself.

Before its arrival, Europe resembled a patchwork of exams and rating scales that refused to align. The CEFR brought order to that chaos by shifting attention from what learners know about a language to what they can do with it. It provided a neutral reference for teaching programs and language tests, promoting transparency and mutual recognition across borders.

Today, CEFR levels serve as the de facto global standard for describing language proficiency levels—used in universities, migration offices, and job applications far beyond Europe. Yet the framework remains voluntary: teachers, schools, and exam boards are free to interpret it. As a result, the lines between levels can blur, sometimes stretching to flatter students or compressing their abilities into neat but imperfect categories.

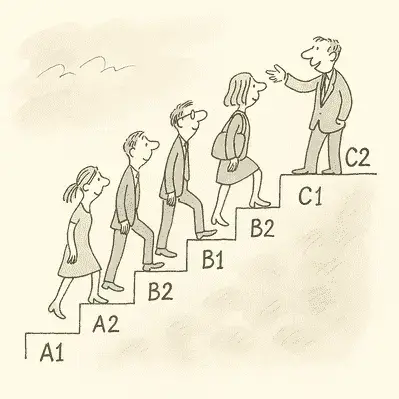

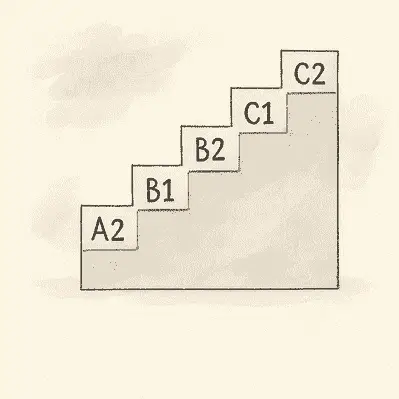

2. The Six CEFR Levels – A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, C2

The CEFR levels are divided into three broad categories—Basic User (A1–A2), Independent User (B1–B2), and Proficient User (C1–C2). Each level defines the learner’s ability to communicate, from mastering very basic phrases to managing complex subjects and abstract discussions.

| Level | Descriptor | Example of Competence |

|---|---|---|

| A1 – Breakthrough | Can understand and use very basic phrases and basic personal expressions related to immediate needs. Can engage in a simple and direct exchange of information when the other person talks slowly and clearly. | Introduce oneself, share personal details, and ask about family information or immediate needs. |

| A2 – Waystage | Can understand sentences and familiar everyday expressions and phrases related to familiar matters regularly encountered in daily life. Can handle simple and routine tasks involving personal interest or work, and manage situations that may arise whilst travelling. | Describe local geography, talk about routines, or carry out simple and routine tasks like shopping or traveling. |

| B1 – Threshold | Can describe experiences, understand the main ideas of clear input, use cohesive devices, and produce simple connected text on topics of most immediate relevance. | Explain plans, narrate events, and answer questions while travelling or working abroad. |

| B2 – Vantage | Can interact with native speakers fluently and discuss complex situations or technical discussions. Can produce detailed text and identify implicit meaning. | Participate in meetings, summarise main points, and discuss issues of professional purposes. |

| C1 – Effective Operational Proficiency | Can use language flexibly and effectively for academic or professional purposes. Can recognise implicit meaning and deliver a well-structured and coherent presentation. | Write reports, analyse complex subjects, or debate at a professional level. |

| C2 – Mastery | Can understand virtually everything heard or read and reconstruct arguments from various sources. Can express finer shades of meaning precisely and differentiate between nuances. | Interpret discussions, adapt tone for context, and communicate with ease virtually anywhere. |

The a1 a2, b1 b2, and C1–C2 categories represent developmental stages from basic user competence—using basic phrases aimed at practical communication—to advanced proficiency, where speakers handle complex text, use language flexibly, and differentiate finer shades of meaning in any relevant language.

3. Describing Language Proficiency

The CEFR describes language skills using “can-do” statements that outline what learners can achieve. This approach focuses on communicative function rather than grammatical accuracy. Examples include:

- Can use very basic phrases and basic personal information to meet an immediate need.

- Can take part in a simple and direct exchange of information on familiar and routine matters.

- Can communicate about personal interests, work, and the immediate environment.

- Can handle language flexibly in conversations with native speakers.

- Can manage routine tasks requiring clear, predictable communication.

- Can use language flexibly and effectively to express opinions and negotiate.

This method of describing language ability makes the CEFR an important way to refer to second language fluency. It helps teachers design teaching programmes, students monitor progress, and exam boards align language exams with an international standard.

4. Role of the Council of Europe

The Council of Europe created the CEFR to foster cooperation and mutual understanding through languages. It is intended to develop a Common European Framework that could apply across borders, cultures, and European languages—and, today, even to languages like Arabic and Chinese languages.

By establishing clear language levels, the Council developed a universal framework for foreign language teaching, testing, and assessment. The CEFR’s model has since influenced global systems such as the Interagency Language Roundtable Scale, highlighting its relevance beyond Europe.

5. CEFR and Communication in Real Life

The CEFR connects linguistic ability to real-world tasks—from simple and routine tasks like introducing oneself to more complex situations such as business negotiation or academic writing. Learners develop from using familiar everyday expressions and very basic phrases in regular interaction to discussing complex subjects fluently.

A learner at A1 might focus on personal details and family information, while a B2 speaker can discuss professional purposes or take part in technical discussions. At C2, learners can interpret implicit meaning and show mastery through coherent presentation and refined organisational patterns of thought.

The CEFR also applies to learners of the English language, French, German, or any second language, ensuring the same global scale for evaluating performance in every target language.

6. Why the CEFR Matters

For Learners

For learners, the CEFR offers a clear frame of reference. Its CEFR levels show what progress looks like—from handling familiar matters as a basic user to engaging in complex subjects with confidence. It helps learners understand where they stand and what skills they still need, rather than prescribing how they should get there.

For Teachers and Institutions

For teachers, the CEFR is an evaluative guide, not a teaching method. It provides a shared vocabulary for describing language ability and assessing progress across contexts. Teachers use it to place learners within a language reference, not to specify classroom practice. The framework describes outcomes—what learners can do—leaving the how entirely up to pedagogy.

For Employers and Policymakers

For employers and institutions, CEFR levels act as a common benchmark of language fluency. A notation like “B2 French” or “C1 English” conveys a reliable sense of competence that transcends local grading systems. Because it’s widely accepted, the framework facilitates academic recognition, professional mobility, and transparent comparison across borders.

A Note on Realism

While the CEFR levels describe foreign language competence, the C1 level aligns closely with the descriptors of native speaker communication—particularly in fluency, coherence, and command of complex ideas. It represents a specialised, high-functioning mastery of language often applied in professional or academic contexts.

Reaching a C1 level in a non-immersive context—and we are not referring to classroom learning—is almost impossible. This should not be confused with passing a C1 exam, which can be prepared for through study and strategy. True C1 proficiency requires sustained exposure, interaction, and the kind of natural adaptation that only immersion can provide.

7. The CEFR as a Global Reference

Today, the CEFR influences second language instruction across all regions. It applies equally to languages spoken in Europe and outside of Europe, including English and others such as Arabic, Spanish, or Mandarin.

Its flexible structure allows adaptation to diverse teaching courses and language exams while maintaining a consistent reference for languages. The CEFR’s focus on communication, context, and describe experiences makes it an invaluable model for educators worldwide.

8. The CEFR and Tests

The relationship between language tests and the CEFR levels is, to put it mildly, ambiguous. Some examinations are explicitly designed around the CEFR scale; others merely nod to it across a polite distance.

Take the IELTS, for instance. It predates the CEFR Levels, relying on its own point system rather than the CEFR’s descriptive levels. The numerical bands of IELTS can be mapped onto the CEFR grid, but this is more a matter of statistical correlation than conceptual design.

Other examinations—such as the DELF/DALF in France or the FIDE test in Switzerland—build their evaluations directly on the CEFR. Yet, even here, the resemblance is more family than identical twins. The DELF B1, for example, tends to assess more technical control of French grammar and syntax, while the FIDE B1 focuses on whether candidates can actually use the language in everyday life. Both claim the same CEFR level, but their lenses are set to different focal lengths.

Academic exams—like the GCSEs, IGCSEs, IB, and A levels—take a further step back. They reference CEFR descriptors to communicate approximate difficulty but remain guided by national curricula that prize communicative use and educational outcomes rather than CEFR compliance.

From all this, one simple truth emerges: the CEFR was never meant to police testing. It was designed to describe language ability, not to enforce it. While its terminology has become a global shorthand used by schools, teachers, and examining bodies, each interprets it with its own inflection. Thus, even an international standard, when filtered through a hundred systems, inevitably develops a local accent.

9. Summary

The CEFR levels defines how we describe, teach, and measure language proficiency. Its six CEFR levels—from a1 a2 to b1 b2 and beyond—illustrate the journey from learning very simple phrases to mastering complex subjects and coherent presentation.

Developed by the Council of Europe, this Common European Framework unifies second language instruction, language assessments, and academic standards under a single global scale. By describing language ability transparently, it enables learners to progress from simple and routine tasks to fluent communication across borders and cultures.

For teachers, learners, and employers alike, the CEFR remains the most practical, reliable, and universal reference for languages—a system that connects familiar matters regularly encountered in daily life to the highest levels of linguistic mastery.