*Comprehensible input is often presented as a universal solution in language teaching. This article examines what the theory actually claims, where it is misunderstood, and why adult learners, adn teachers complicate its application.

Comprehensible input language teaching

Comprehensible Input in Practice: Misinterpretations, Limits, and Adult Learners

Introduction

Paradoxically, while comprehensible input is a central concept in second language acquisition, it is also one of the most frequently misunderstood ideas in language learning and language teaching.

Few theories have been so widely cited while being so unevenly applied.

Much of the ongoing debate surrounding comprehensible input does not arise from the theory itself, but from how it has been interpreted, simplified, or operationalized by language instructors—often with the best of intentions and the loosest of definitions.

Within applied linguistics, comprehensible input is therefore frequently discussed as if it were a complete instructional approach for learning a new language or a foreign language, rather than as a theoretical explanation of how language input supports language development.

A conceptual frameworks for language acquisition designed to explain why language is acquired is repeatedly asked to explain how a lesson should be run on Tuesday at 10 a.m.

This review article examines where interpretations diverge, why the theory encounters limitations in classroom practice—particularly for adult learners and second language learners—and how assessment-driven education systems complicate its application.

The aim is not to prove or refute comprehensible input, but to clarify its scope within second language studies and to separate theoretical claims from classroom realities.

Key takeaways

- Comprehensible input explains how language acquisition occurs; it does not issue lesson plans.

- Input-only interpretations often assume adult learners learn like children, minus the toys and plus the deadlines.

- Adult learners typically benefit from implicit exposure and explicit reflection, despite persistent hopes for shortcuts.

- Input and output interact; language does not politely wait to be spoken before being understood—or vice versa.

- Assessment systems often reward visible knowledge, even when second language acquisition prefers to remain quietly invisible.

Language acquisition – When Theory Becomes Method

Key point: Comprehensible input theorises mechanisms of acquisition, not instructional procedures.

A recurring issue in discussions of comprehensible input is the tendency to treat it as a self-contained teaching method rather than as a theory within second language acquisition research.

In classroom teaching, this often leads to the assumption that exposure to input alone—through listening, immersion, or reading —is sufficient for language proficiency, second language performance, and even advanced language use.

This interpretation extends beyond the original claims associated with the input hypothesis.

Comprehensible input is a theory of second language acquisition, not a procedural framework for language learning and language teaching.

Like universal grammar, it was formulated to explain underlying mechanisms of language acquisition rather than to prescribe classroom techniques or instructional sequences.

It theorises and explains how linguistic systems are internalized, not how long a worksheet should be.

When translated directly into language classroom practice without additional structure, the theory is frequently expected to resolve issues such as grammar, understanding of grammatical rules, speaking, writing, or exam preparation—outcomes it was never conceptualised to guarantee, let alone schedule.

Language learning – Strong and Moderate Interpretations

Interpretations of comprehensible input tend to fall along a spectrum, but the distance between its ends is larger than it first appears.

Strong interpretations treat language input as both necessary and sufficient for second language acquisition, largely independent of learner age, goals, context, or learning environment. In this view, exposure does most of the work, and anything else is at best optional, at worst a distraction.

More moderate interpretations view comprehensible input as a foundational condition for language acquisition, but not a complete account of learning. Input matters—deeply—but it must be complemented by other mechanisms described in other theories of language learning, particularly once learners move beyond early stages.

On the other end of the spectrum are teachers and academics who believe the theory is completely wrong and that language acquisition is primarily internalized through the direct study of its theory or grammar.

Approaches

Strong interpretations often lead to approaches based almost exclusively on exposure, minimizing explicit instruction, feedback, and opportunities for language production. The assumption is that if learners are exposed to enough comprehensible input, everything else will eventually sort itself out.

This position may resemble naturalistic acquisition in children acquiring their native language or first language, often assumed to occur within a critical period that adult learners have already passed. Applied to adults, however, it raises immediate concerns. Adults operate under time constraints, performance expectations, and institutional demands—conditions that rarely feature in playgrounds, kitchens, or bedtime routines.

*This is a discussion for another article, but adults often do not have the ideal schedule and timeframe for classes. That said, the approach is not only limited to the classroom but also an overall theory of second language acquisition in daily life.

Suggested application

In The Natural Approach: Language Acquisition in the Classroom (1983), Krashen himself does not present such a passive model. He places comprehensible input alongside concrete language classrooms examples that involve strong participation and constant back-and-forth between student and teacher. New material is made comprehensible without resorting to translation, relying instead on context, interaction, repetition, and meaning.

Crucially, the theory as described in this practical approach is never intended to be a stand-alone listening model. It does not argue that students merely listen and wait. Rather, it proposes that learners acquire language when they understand what they hear—and that understanding naturally leads to response, participation, and communication.

*It’s importnat to note that the research was primarily carried out in the USA with non-english speakers who intended to learn English, the native language of the country. When learning a language such as French, learning Spanish, in an envioment where the studnet does not get daily posibility of exposure outside of class, this also impacts the learning curve and input.

The difficulty with Krashen’s work lies on multiple fronts. Two are particularly significant.

Language teachers and the limits of application

On the one hand, the theory has been widely misunderstood and, in many cases, simplified to the point of caricature. On the other—and this is far less discussed in language teaching—most teachers do not have the training, and sometimes not even the institutional conditions, to apply the approach with any real precision.

While the theoretical foundations have remained largely unchanged since their formulation in the 1980s, the conditions under which language learning takes place have changed considerably. Teaching staff are, on average, less extensively trained.

In many contexts, a teacher can be certified after roughly 120 hours of training, with only a handful of hours of supervised classroom practice. By contrast, competent application of a comprehensible input–based approach would require hundreds—if not thousands—of hours of sustained classroom experience.

Foreign language learning in non-native environments

At the same time, demand for language learning classes has increased dramatically, particularly in non-native environments. Learners are often surrounded by other non-native speakers, with limited access to meaningful natural exposure outside and instructional setting. Under these conditions, input is neither abundant nor optimal, and the assumptions underlying naturalistic exposure become increasingly fragile.

As discussed later in this article, implementing comprehensible input well is neither intuitive nor effortless. It requires sustained pedagogical training, continuous real-time adjustment, and a high level of classroom skill—realistically, hundreds of hours of training, not a revised textbook, a new label, or a well-meaning intention.

Where this level of expertise cannot reasonably be expected, the alternative is not abandonment of the theory but systematisation: carefully designed language learning materials and structured learning environments that guide both learner and teacher—or facilitator.

Such systems aim to optimise input and output conditions, reducing reliance on individual teacher intuition while preserving the core principles of comprehensible input.

A further complication arises outside formal teaching environments altogether.

An increasing number of learners now engage with language learning in non-teacher settings: through self-study, mobile applications, online platforms, or independent exposure.

In principle, this should be fertile ground for comprehensible input. In practice, it often reproduces the same misunderstandings found in instructional settings—sometimes more efficiently.

Many applications and self-learning systems equate comprehensible input with exposure alone. Learners are shown language, asked to listen or read, and encouraged to repeat the process—often without being required to do anything meaningful with a new word. Interaction with meaning, however, is frequently minimal, leaving little room for problem solving, focusing attention on meaning, or meaningful decision-making by the learner.The learner is exposed, but not required to do very much with what they hear.

To be clear, the achievement of these tools should not be dismissed. Designing systems that retain learners, motivate repeated use, and encourage consistent engagement through gamification is already an enormous success. Getting people to come back at all is no small feat.

The problem is not motivation; it is content.

Practising that the pink elephant is in the tree may be memorable, but it is not meaningful. It does little to anchor language acquisition in realistic communicative contexts or to support the internalisation of sounds, structures, and usage as they occur in natural speech.

Similarly, reading and translating content may increase explicit knowledge, but it does not reliably lead to the internalisation of words as sounds embedded in fluent language.

Comprehensible input is not about seeing language, nor even about recognising it. It is about understanding messages well enough that language begins to organise itself internally. This process is supported not only by listening, but by interaction—by responding, reformulating, and engaging with meaning. Listening without engagement remains exposure; it does not become acquisition simply by repetition.

In this sense, many self-learning environments replicate the same reduction of comprehensible input found in poorly implemented language class models: language exposure without interaction, content without consequence, and exposure without integration.

Adult learners are not children

Key claim: Arguments against comprehensible input claim that adult learners acquire language under constraints that make input-only approaches insufficient on their own.

A common argument against input-only interpretations points to differences between adults and children learners.

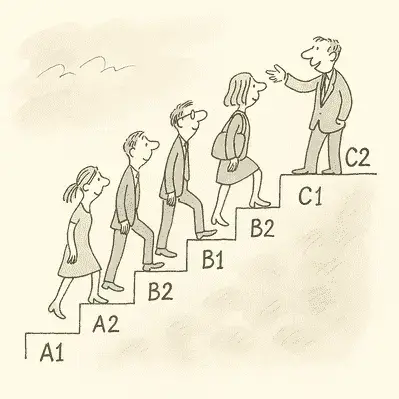

The claim is straightforward: adults arrive with a fully developed first language, established cognitive habits, more developed cognitive processes, and explicit goals. They are not linguistically empty-handed, and they rarely have the luxury of time.

From this perspective, adult language learning is often goal-driven—passing exams, functioning professionally, reaching a target level—often all at once. Relying on implicit exposure alone is therefore described as inefficient, or at least optimistic.

Supporters of this view argue that adults, while still capable of implicit language acquisition, also benefit from metalinguistic awareness, explicit rule learning, and structured explanation—capacities that children acquiring one language have not yet had reason to develop.

Empirical limits and the problem of evidence

A further complication—acknowledged by Krashen himself—concerns the nature of evidence in linguistics and language acquisition research.

Critiques of comprehensible input frequently point to a lack of definitive, long-term empirical proof. Strictly speaking, this observation is accurate. However, the argument is often asymmetrical. The same standards used to question comprehensible input are rarely applied with equal rigor to the alternative theories being proposed.

Despite the existence of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of studies in linguistics, there are no large-scale, long-term investigations with tightly controlled variables: the same teachers, the same instructional methods, comparable learner profiles, and consistent outcome measures.

In practice, studies vary widely in teacher training, learner nationality, target language, institutional context, duration, and evaluation criteria.

As a result, much of the available research is informative but not cumulative. Individual studies may be rigorous in isolation, but their findings are difficult to aggregate into definitive conclusions about second language acquisition processes.

This limitation is not unique to comprehensible input. It applies broadly across theories in second language acquisition studies. In this sense, comprehensible input is not disproven, but constrained—like most acquisition theories—by the methodological limits inherent in studying learning and teaching in instructional settings.

The same evidentiary constraints apply to claims about the language acquisition device, which by definition concern internal mechanisms that cannot be directly observed or easily isolated in classroom research.

The absence of definitive proof, then, complicates interpretation rather than settles the debate, leaving most claims—on all sides—more suggestive than conclusive.

Input and output as interacting processes

Key claim: Comprehension and production form a feedback loop rather than a linear sequence.

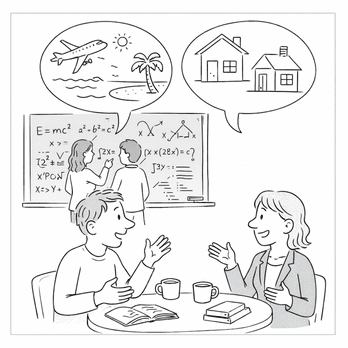

Research in second language acquisition, drawing increasingly on insights from cognitive science, treats comprehension and production as two interacting processes within broader language development, rather than as competing or sequential stages.

Learners often understand more than they can produce—a reassuring observation until production is actually required. At that point, the limits of comprehension-only engagement become visible.

Output plays a role in consolidating linguistic knowledge. Speaking and producing sentences forces learners to test hypotheses, notice gaps, and refine form—processes that are difficult to trigger through passive exposure alone.

Crucially, this does not contradict the input hypothesis. Nothing in Krashen’s formulation argues for listening instead of interaction, nor does it propose language development through silence. The claim is that comprehension drives acquisition, not that production is irrelevant or should be postponed indefinitely.

Rather, the evidence suggests that language does not develop in silence forever. Comprehension enables production, and production, in turn, sharpens comprehension. Input and language production therefore operate in a feedback loop, a view reinforced by the output hypothesis, the interaction hypothesis, and sociocultural theory, all of which emphasise interaction, feedback, and engagement with meaningful examples in second linguistic performance.

Language acquisition, learning, and the role of assessment

Another point of tension lies in the distinction between second language acquisition and formal assessment.

Educational institutions often prioritize measurable outcomes, discrete words, vocabulary, and explicit grammar knowledge.

Students want reassurance that they are learning, that they can create new sentences, and that they understand what is being taught—preferably by Friday.

However, learning a second language is not a linear process.

Language performance, language use, and communicative ability develop unevenly and at inconvenient speeds.

Even a native speaker continues to adapt language over time.

Examinations, by contrast, often assess knowledge about language rather than sustained communicative ability, creating a mismatch between acquisition processes and institutional expectations in an instructional setting.

This tension places pressure on language teachers, who must balance theory, resources, and curriculum demands while ensuring students understand both form and meaning—often simultaneously.

Conclusion

Much of the ongoing debate surrounding comprehensible input arises from a persistent conflation—not only between theory and method, but between input and listening.

Comprehensible input is not a theory addressed solely to language educators, nor is it confined to instructional settings. It is one segment of a broader theory of how humans acquire language, whether in formal education, informal interaction, or independent learning. Its relevance extends equally to language classes, self-study environments, and everyday language exposure.

It is important to restate this clearly: comprehensible input is a segment, not a stand-alone system. It is certainly one of the more compelling and influential parts of the theory, which may explain why it is so frequently singled out. But it was never intended to operate in isolation.

The core misunderstanding is the belief that comprehensible input advocates listening alone. It does not. The theory instead describes acquisition as emerging from two processes—understanding and use—rather than from listening in isolation.

What the theory proposes is that language is acquired when learners interact with material they understand. Listening is one channel through which input is delivered, but comprehension—not passive exposure—is the operative mechanism.

This immediately raises a practical question: how can learners understand without already knowing the words? The answer is not circular, but contextual—and it is addressed in a separate article focused on application. Understanding can emerge through context, redundancy, visual and non-verbal cues, interaction, prior knowledge, and, increasingly, through modern tools that scaffold meaning without replacing it with translation.

Crucially, comprehensible input is not a listening-only theory, nor does it exclude output. Output is not treated as the starting point of acquisition, but it is never removed from the process. Comprehension gives rise to production, and production, in turn, refines comprehension. The persistent conclusion that comprehensible input requires silence is not derived from the theory itself, but from its repeated misinterpretation.

When understood on its own terms, comprehensible input describes a dynamic process: understanding leads to engagement, engagement leads to use, and use reshapes understanding. The real challenge, then, is not whether the theory applies, but how to design learning environments—inside or outside instructional settings—that make understanding possible, meaningful, and consequential.

That question belongs not to theory alone, but to pedagogy, design, and practice.

About My Linguistics

My Linguistics is a language training center based in Geneva, Switzerland. We’re passionate not just about teaching languages, but about understanding how people learn. Our mission is to explore the connection between learners, learning processes, and effective teaching strategies—to improve outcomes and create meaningful learning experiences.