From Theory to Practice: A Principled Application of Comprehensible Input Language Learning

From Theory to Practice: A Principled Application of Comprehensible Input Language Learning

Introduction

Comprehensible input provides one of the most important theories for how second language acquisition happens. Yet despite its prominence in research and language teaching discourse, its translation into effective practice remains uneven and frequently disappointing for many language learners.

This difficulty does not stem from any lack of explanatory power in the theory itself, but from structural constraints within education systems, limited pedagogical training, and persistent misunderstandings about what comprehensible input actually requires in real learning conditions.

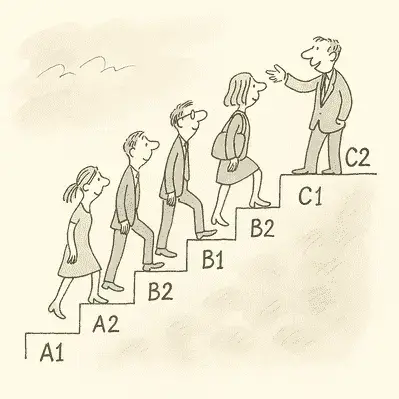

Within second language acquisition research, comprehensible input describes how language input, when understood, drives language acquisition and gradually leads to increased language ability. It theorizes how learners acquire second languages. Too often, however, it is treated as a complete method rather than a theoretical principle—one expected to produce immediate results across classrooms, self-study contexts, and independent language learning environments.

This article examines why implementing comprehensible input in real learning conditions remains challenging and outlines the My Linguistics approach as a principled adaptation of the theory—one that preserves its core insights while addressing the practical limitations that arise in both instruction and independent language learning.

Definition: Comprehensible input theorises how language is acquired through understanding meaning, not how language should be taught.

Article at a glance

- Comprehensible input theorizes how language acquisition occurs, but it is not a complete teaching method in itself.

- Understanding meaning—not studying linguistic theory—is the core condition for language acquisition.

- Listening comprehension plays a foundational role in early and intermediate language development.

- Implementing comprehensible input in real learning conditions is structurally and pedagogically challenging.

- The My Linguistics approach applies the principles of comprehensible input in a structured, practice-oriented way.

Our position on comprehensible input

Our position: My Linguistics treats comprehensible input as a guiding principle, not a complete teaching method.

To be clear, My Linguistics is not a theory based exclusively on comprehensible input from a strict Krashenian perspective. The work of Stephen Krashen articulated and consolidated a body of research that both predates his work and continues to inform future research. His contribution, specifically comprehensible input, theorises that language acquisition occurs when learners engage with new material that they can understand at the level of overall meaning, rather than through explicit knowledge of linguistic theory.

What we fully endorse, however, is the central claim that building listening comprehension plays a foundational role in language acquisition. In our view, listening comprehension is one of the primary engines of successful language acquisition.

This claim is easy to state and deceptively complex to operationalize.

Why listening is foundational

Key claim: Listening comprehension enables language learners to construct meaning before they are able to produce language.

At early stages of learning, language learners with limited productive vocabulary can nevertheless participate in limited but functional interactions, particularly in supportive or familiar contexts. These exchanges may not be linguistically rich from the learner’s side, but they can still be communicatively effective. This is not because learners know grammar rules, but because general contextual comprehension allows them to orient themselves within an interaction and interpret intent.

As proficiency develops, this effect becomes more pronounced. Context increasingly supplies meaning, enabling language learners to infer, reinterpret, and disambiguate new language even when specific words or forms remain unfamiliar.

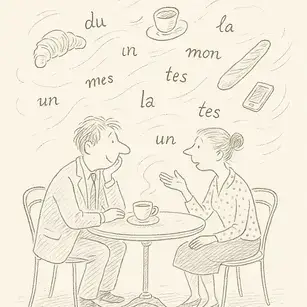

Language does not convey meaning through isolated words or grammatical forms alone. Words acquire meaning through their use in constructions and contexts, often carrying multiple possible interpretations. Context is not an accessory to meaning. It is a central mechanism through which meaning is constructed and interpreted.

For example, in English, the word way changes meaning depending on its surrounding structure: This is the way to the house refers to a physical route, while There is no way I’m going to the house expresses refusal or impossibility. The word itself remains the same; its meaning emerges from the construction and context in which it is used.

French offers similar patterns. Common verbs such as être and avoir appear in a wide range of constructions whose meanings depend on their syntactic and contextual environment. Phonetic ambiguity further increases reliance on context: when speaking, the word prêt in French may refer to readiness, a loan, or, in certain constructions, a location—distinctions that can only be resolved through contextual interpretation.

Attempting to manage this complexity through word-by-word explanation or memorization of vocabulary lists misunderstands how language functions in use. Meaning does not arise from vocabulary items in isolation, but from phrases, constructions, and situations in which language is embedded.

Context, therefore, is not an accessory to meaning. It is a central mechanism through which meaning is constructed and interpreted.

Structural obstacles to application

In practice, many teachers are not trained in delivering comprehensible input in a systematic or sustained way.

Many teacher education programs continue to emphasize explanation, instruction, and learning grammar rules rather than managing language input at the learner’s current level. As a result, grammatical structure, grammar rules, and explicit grammar instruction often dominate the classroom, even when teachers claim to follow input-based approaches.

This structural mismatch explains why comprehensible input is frequently reduced to isolated listening activities, reading exercises, or videos rather than functioning as the foundation of instruction. Students hear a great deal of language, but little of it is calibrated so that students understand meaning at their own level.

Even when teachers accept the theory in principle, common instructional formats undermine its application. Extended explanations, teacher-dominated speech, and abstract discussions about grammar do not automatically create more comprehensible input.

As Krashen argues repeatedly, language acquisition requires language learners to pay attention to meaning first; input must be meaningful, engaging, and processed for comprehension—not merely heard.

Delivering comprehensible input consistently requires far more than goodwill. It demands careful sequencing, repeated exposure, focused attention, and constant verification that students understand.

Developing this ability typically requires extensive guided practice, well beyond what most teacher training programs provide.

A common misunderstanding in contemporary discourse

In contemporary language teaching discourse, it is often claimed that comprehensible input has already been fully integrated into modern pedagogy through a balanced mix of listening, reading, speaking, writing, and explicit instruction.

This position reflects a persistent misunderstanding affecting both teachers and independent language students.

Comprehensible input cannot be reduced to reading alone without significant limitations, particularly in the early stages of acquiring a new language or a foreign language. While reading supports vocabulary growth and grammar awareness, it does not impose the same real-time processing demands as listening. Language acquirers attend to language differently when they hear it unfold, in contrast to when they decode written words.

For beginners learning languages, auditory input plays a central role. People studying languages must hear how words connect, what they sound like, where people add stress to sentences, how meaning unfolds in conversations, and how native speakers structure speech.

This misunderstanding leads to approaches where learners are exposed to large quantities of text, videos, or isolated examples without sufficient context, stories, or opportunities to interact with meaning. Input exists, but learners lack access to it.

The My Linguistics approach: Listening as the primary objective

The My Linguistics approach emerged both independently of and in dialogue with comprehensible input theory, including insights from the affective filter hypothesis. Rather than applying the theory dogmatically, it treats comprehensible input as a supporting principle for how language learning can be structured in practice.

At its core, the approach prioritizes listening as the primary objective. This does not mean passive listening. Learners engage in focused listening activities designed so that input remains comprehensible at their own level. Speaking is introduced deliberately—not to force fluency, but to confirm understanding.

Learners first encounter the target language through meaningful contexts: short conversations, structured examples, and guided dialogues. Repetition is used strategically—not as rote memorization, but as perceptual training and repeated exposure that supports comprehension and language development.

This reflects a core idea Krashen argues consistently: people acquire language when they understand messages, not when they consciously study grammar in isolation.

Why listening alone is not sufficient

Listening alone can create an illusion of progress when it is not accompanied by opportunities for interaction or production. Learners may feel that they understand because the input sounds interesting or familiar, yet remain unable to respond or participate meaningfully.

This becomes evident when learners are asked to respond. The inability to reproduce even simple phrases reveals gaps in perception, vocabulary, or grammatical structure. In this sense, speaking functions as a diagnostic tool within the learning process.

By requiring learners to respond, reformulate, or react to what they hear, the My Linguistics approach transforms listening into an active process. This supports deeper comprehension, stronger retention, and the gradual development of proficiency—without prioritizing performance over understanding.

Speech as a tool for comprehension

Within this framework, output is not treated as the final goal of language learning, but as a mechanism that supports comprehension. Learners produce output in order to verify whether they truly understand the input they hear.

This preserves the central claim of comprehensible input—comprehension precedes production—while aligning with findings from cognitive science suggesting that controlled output can sharpen perception and support the language acquisition process.

Speech here is not about immediate fluency or perfection. It is about making sense of language and engaging meaningfully with a new language.

Conclusion

The My Linguistics approach does not reject comprehensible input, nor does it attempt to replace it with a competing theory. Instead, it treats comprehensible input as a foundational principle of language learning that must be implemented with structure, intention, and pedagogical discipline.

By prioritizing listening, using speaking as a tool for comprehension, and acknowledging the limits of passive exposure, the approach supports optimal language acquisition while remaining grounded in real learning conditions.

In doing so, it offers language learners, teachers, and students a coherent framework for successful language learning—whether they are learning a new language independently, studying a foreign language in a class, or seeking an effective way to acquire language through meaningful interaction rather than memorization.

About My Linguistics

My Linguistics is a language training center based in Geneva, Switzerland. We’re passionate not just about teaching languages, but about understanding how people learn. Our mission is to explore the connection between learners, learning processes, and effective teaching strategies—to improve outcomes and create meaningful learning experiences.